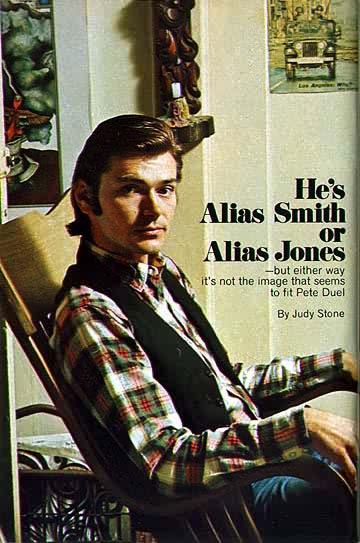

- HE'S ALIAS SMITH OR ALIAS JONES--but

either way it's not the image that seems to fit Pete Duel

- by Judy Stone

- TV Guide, May 15, 1971

In

1965, Peter Deuel had a private five-year plan. Five years in

Hollywood to show his stuff, and then back to Broadway to name

his price and his play. Instead he mushed through the goo of

Gidget and Love on a Rooftop, suddenly whipped

into political action and then subsided into a Zenlike meditation.

He emerged in a mood to simplify his life, stripped away some

nonessentials and changed his name to Pete Duel.

In

1965, Peter Deuel had a private five-year plan. Five years in

Hollywood to show his stuff, and then back to Broadway to name

his price and his play. Instead he mushed through the goo of

Gidget and Love on a Rooftop, suddenly whipped

into political action and then subsided into a Zenlike meditation.

He emerged in a mood to simplify his life, stripped away some

nonessentials and changed his name to Pete Duel.

It sounded terse. Clean-cut. The right

name for the new role. Pete Duel stars as Hannibal Heyes in Alias

Smith and Jones, ABC's new humorous Western series. Heyes

is a wide-eyed safe-cracker in the dying days of the Old West.

He wants to go straight, more or less, and win amnesty along with

his pal, Ben Murphy. Murphy is the cool gun toter. One is alias

Smith, the other alias Jones. Which is which doesn't really matter.

Duel plays it Puckish, displaying his dimples.

Except that it's the wrong image for the

real Duel. There's nothing either clipped like the new name or

ingratiating like the new character about the introspective young

man. He lived, until lately, in a state of congenial clutter in

a $65-a-month, one-and-a-half room garage-top apartment in a middle-class

Los Angeles neighborhood. [He has since moved to larger, more

rustic and ramshackle quarters, but equally simple.--Ed.]

Duel

is wary about interviews. "This is a part of the business

I find amusing and also frightening," he says, pushing his

straight, longish dark hair behind his ears. Wearing blue jeans

and a blue-and-white T-shirt, he sits in an antique rocker, bare

feet tucked under him. "There's a kind of reality to all

this press-personality myth, but fame in show business is not

in proportion to actual achievement. What happens so often is

that things get out of sync."

Duel's determination to preserve a certain

privacy shows when he introduces his girl, Diane. First name only,

please, they both insist firmly, but warmly. She is tall, slim,

serene-looking, with long brown hair and a long, intelligent Modigliani

face. She had been working as a TV producer's secretary when they

met on location for The Psychiatrist pilot in which Duel

played a junkie. They share a love of the outdoors and a desire

to preserve it from further encroachments, an interest in the

world outside the TV tube, and a taste for health food.

While Pete checks on the activity of their

three dogs outside, Diane whips up a sample drink for me: natural

wheat-germ oil, lecithin, a real banana, molasses, Malabar (desiccated

liver and defatted, defibered beef organs), brewer's yeast and

dolomite (magnesium and calcium). I drain my cup but pledge my

allegiance to Julia Child.

The

room itself says a lot about Duel. Behind the corncob-decorated

front door, a bulletin board holds a dozen Eugene McCarthy campaign

buttons (and one for George Wallace, received in a trade). A blue-and-white

quilt-covered bed takes up most of the space, along with a sofa

covered with red-and-white Indian cotton cloth. Classical records

and books are jammed together at the far wall and Diane explains

that the book on obstetric practice is not a reflection of the

fact that Duel's family is packed with doctors; it was given to

him when he had his first major film role in "Generation,"

with Kim Darby as his pregnant wife.

Mixed in a crazy jumble on the shelves

are an art-book series, Felix Greene's "Vietnam! Vietnam!,"

"The Psychology of Self-Esteem" by Ayn Rand's No. 1

disciple Nathaniel Branden, "House Made of Dawn" by

the American Indian Pulitzer-Prize winner N. Scott Momaday, "How

to Buy Stocks," "Look Homeward, Angel" and the

complete works of Shakespeare. Thoreau's "On Man and Nature"

and Dylan Thomas's poetry have the place of honor in the bathroom,

surrounded by vitamin and health food pills.

Paintings decorate the walls, including

Duel's own delicate, whimsical sketches, a wildly colored surrealistic

series, one "Keep the Faith" sign and a now obsolete

admonition to "Boycott Grapes." A door panel is covered

with clippings on civil rights. Over a photo of demonstrators

being turned away from the First Methodist Church in Americus,

Ga., Duel has written "Worship Next Sunday. It's the American

Way."

When Duel, 30, finally returns, he introduces

the dogs. The black-and-blue Australian sheep dog is Shoshone

("named for the Indian tribe--the WASP trying to atone for

his guilt"); a toy poodle called Champagne and "the

crazy-looking one is Carroll, for Lewis Carroll."

Still

ill at ease about the interview, Duel turns on the TV set for

the Saturday football game and looks yearningly from time to time

at the play soundlessly flashing by. Football is a passion that

has come comparatively late. He was a loner who liked to walk

in the woods when he was growing up in Penfield, N.Y., a one-stoplight,

politically conservative farming community that now serves as

a suburb for Rochester. His father was the town's general practitioner,

his mother the nurse.

Although Pete started acting in kindergarten,

the idea of becoming a professional was "too weird to contemplate."

He was an indifferent student but felt he should get a college

education. He considered going to Annapolis to become a Navy pilot,

but finally decided against it.

"It's probably the best thing that

ever happened to me," he says now. "I’d probably

have nosed down in Vietnam with a jet wound around me."

He did poorly at St. Lawrence University.

At the end of his second year, Dr. Deuel saw him in "The

Rose Tattoo" and said sympathetically. "If you want

to go to school, why don't you go to drama school instead of wasting

my money here?"

Pete auditioned at the American Theater

Wing school in New York City, fell in love with the town, went

to classes on time and buckled down to work. "I realized

I knew nothing about acting. But all of a sudden I committed myself

and recognized that this is an art and it isn't easy. That's when

the work began, the pain, the self-searching, the asking 'What

do I do? What is acting?' It's only in the last two years that

I've started to get some answers."

After graduation, he performed in a Family

Service play about syphilis, got his Equity card through a short-lived

Shakespearean company, won a small film part in "Wounded

in Action" and understudied Tom Ewell in "Take Her,

She's Mine."

When it played Los Angeles, he decided

to try his luck in TV, get a series and then return to Broadway.

"It worked out well, except that

at the end of the five years, I got Love on a Rooftop.

It was a fine series. It was sentimental without being maudlin,

although every once in a while it got a little sticky. I don't

usually like to watch gooey sentimentality myself, but sometimes

it's a release. It allows you to sit and cry, and you may be crying

for a lot of other things. Many people go through a period when

all they want is reality, the blacker the better. But oh, that's

a heavy burden to carry."

He

carried such a burden for a while during the McCarthy campaign

for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1968. "It was

my first experience as a real activist. I had blinders on before

because I was career-oriented and under contract to Universal.

But after Love on a Rooftop, I felt a vague discontent.

Then that phenomenon took place in New Hampshire and I got involved."

He saw McCarthy as the "philosopher-king"

he wanted for president: someone with the "vision and awareness

of a philosopher, plus political acumen." He stuffed envelopes,

gave out leaflets and stayed on right through to Chicago, where

he found himself face to face with a terrified young National

Guardsman wearing a gas mask and pointing a bayonet at him. "Chicago

was the closest I ever want to come to war," he said. "I

couldn't put a price on the education got from that campaign."

Looking

back on his work as the architect husband in Love on a Rooftop,

he says he didn't know anything about comedy and he still doesn't

know as much as he'd like to. However, his co-star Judy Carne

believes he is one of the few actors with masculine appeal who

can also handle comedy. She watched him progress from a cocky

kid to someone "who doesn't deal on an ego level." "He's

instinctively a giver. He looks into your eyes and a lot of actors

don't. He acts with you and for you and not for himself. That's

a very enviable thing."

Producers vouch for the fact that Duel

can raise hell with the most temperamental of them if a script

is inadequate or the acting not up to his standards. He'll pester

the director with pertinent questions about character motivation.

"I like the challenge of being his

agent," says Marc "Butch" Clavell. "He is

terribly headstrong and willing to take a suspension at the drop

of a hat if the property is not up to par. He's not afraid to

fight with the biggest people, but he's honest and a beautiful

friend. When I was in the hospital, he offered to finance my three

children's education in a private school."

Dave McHugh, a New York composer, recalls

the time they both plunged into the icy Hudson River to save a

strange puppy. Roy Thinnes mentions the wild bird with a broken

leg that Duel took home while they were on location with The

Psychiatrist. Some time later, Pete appeared on the set looking

disturbed and the emotion spilled over into his scene. Thinnes

asked what was wrong and learned that the bird had died that morning.

Duel's ability to bring the feeling in his real life into his

creative work moved and impressed Thinnes.

Duel

himself thinks the best thing he has done so far is his portrayal

of a junkie. "I wanted to show that addicts are not that

different. They are people who are addicted and they're not from

another planet. I wanted to show that Casey was a human being

who didn't like being hooked and was terrified that he was not

going to be able to kick the habit."

Duel, who occasionally used to drink too

much, has given it up now. Like drinking, he says, addiction comes

not so much from need to escape devastating personal realities

but from the desire to escape daily boredom.

Daily boredom is not one of Duel's problems

these days. Whether he's alias Smith or alias Jones, he's working

hard and gradually beginning to feel confident that he can actually

become the consummate actor he's been struggling to be.

Back

to Articles List

In

1965, Peter Deuel had a private five-year plan. Five years in

Hollywood to show his stuff, and then back to Broadway to name

his price and his play. Instead he mushed through the goo of

Gidget and Love on a Rooftop, suddenly whipped

into political action and then subsided into a Zenlike meditation.

He emerged in a mood to simplify his life, stripped away some

nonessentials and changed his name to Pete Duel.

In

1965, Peter Deuel had a private five-year plan. Five years in

Hollywood to show his stuff, and then back to Broadway to name

his price and his play. Instead he mushed through the goo of

Gidget and Love on a Rooftop, suddenly whipped

into political action and then subsided into a Zenlike meditation.

He emerged in a mood to simplify his life, stripped away some

nonessentials and changed his name to Pete Duel.